1

The title of this memoir, Vietnamese Days, is adapted from the classic fictional quasi-biography of George Orwell, Burmese Days, which is based on his political coming of age as a young man in colonial Burma. Of course the parallel between my learning experiences in Vietnam and Orwell’s life in a very different time and place is strained, but the theme of progressive disillusionment in a grand venture as a result of direct exposure to its flawed assumptions and underlying contradictions is what I had in mind; the British colonial ascendency in one case, and the American Century of global dominance in the other.

As background, let me quote a study of Orwell’s intentions in writing Burmese Days, and how this led to his more famous works. “George Woodcock tied this picture to the Blair [Orwell was a pen name later adopted by George Blair] family as he argued in his Who Killed the British Empire?(1974) that Orwell is held up an example of someone who came from an Anglo-Indian family, but still ultimately rejected imperial service. More important, his writings ‘epitomized the complex feelings of those young educated British who found they could no longer justify involvement in the mechanism of Empire.’ Again, Orwell represented the growing criticism of the Empire on the eve of the Second World War.”[1][/footnote]

“In his magisterial trilogy devoted to the rise and fall of the British Empire, James Morris regarded Orwell as an example of an imperial servant who no longer really believed in the system which he served. Furthermore, Orwell was an example of a ‘softened, perhaps weakened’ imperialist. …W.M. Roger Louis located Orwell along with E.M. Forster (Passage to India, 1924) as figures who might be displayed as more than emblems of disbelief; their two novels “contributed to the anti-Empire spirit of the times.” In other words, Orwell was more than a representative figure, but someone who actively influenced the formation of public opinion. The image of the alienated imperial servant was rendered even more iconic by Niall Fergusson’s Empire (2002). Orwell was included for his inability ‘play world policeman with a straight face.’”[2]

This book makes no claim that I “influenced the formation of public opinion” on Vietnam or any other subject, but the connecting theme is disillusionment with the grand projects of the preceding generation. In my case this included my own father who was a significant contributor to the rise of the United States to a position of hegemonic global leadership, which led the Best and Brightest to conclude that American intervention in Vietnam was essential to preserving America’s position in the world and, thus, its own national security. I was launched into adulthood at a critical moment. I graduated from Yale in 1960 just as the captivating persona of John F. Kennedy was emerging as a dominating national figure. It was Kennedy and his advisors, including my father’s friend and Harvard colleague McGeorge Bundy, who made the critical decisions that launched America on its disastrous intervention in Vietnam.

My initial enthusiasm for JFK was somewhat muted by the fact that my father was Nixon’s primary foreign policy advisor in the 1960 Presidential campaign, and I therefore voted for Nixon. After the election, however, I became increasingly attracted to Kennedy’s charisma and youthful dynamism. Like many others in my generation I was quite willing to “pay any price and bear any burden in the defense of liberty” as Kennedy exhorted us to do in his inaugural address. This memoir is largely about the ways in which my own personal involvement in Vietnam led to a loss of belief in this proposition, and ultimately to the conclusion that American intervention in Vietnam was a tragic mistake, with disastrous consequences for both Americans and Vietnamese.

The Vietnam War was the consequence of a flawed concept called the “Domino Theory” which postulated that in the Cold War confrontation even the most remote and seemingly insignificant ally could not be allowed to fall into the Soviet camp, because it would set in motion a chain reaction of falling dominos (“if Vietnam goes…’) which would ultimately lead to the collapse of the central pillars of the American alliance system, like Japan. The Domino Theory, in turn, derived from the more encompassing Cold War trope, aptly named “The Gospel of National Security” by Daniel Yergin in his classic study of the origins of the Cold War, “Shattered Peace.”

Yergin wrote, “We must remember that ‘national security’ is not a given, not a fact, but a perception, a state of mind.” The Gospel of National Security posits that “Virtually every development in the world is perceived to be potentially crucial. An adverse turn of events anywhere endangers the United States. Problems in foreign relations are viewed as urgent and immediate threats. Thus, desirable policy goals are translated into issues of national survival, and the range of threats becomes limitless.”[3] As a consequence, it becomes impossible to prioritize security commitments because even minor problems can destabilize the entire system of American hegemony. Thus, JFK asserted, “we must pay any price, bear any burden in the defense of liberty.”

America’s experience in Vietnam taught the lesson that the U.S. could not sustain the burden of responding militarily to every challenge in marginal or peripheral areas. Thus it was crucial to prioritize commitments and to carefully assess costs and benefits in responding to perceived challenges, especially on the periphery of America’s sphere of containment surrounding the Soviet Union and China. For both Americans and Vietnamese, the tragedy of the Vietnam War was that the U.S. did not attempt to analyze what was happening in Vietnam itself in any depth. For Washington’s policy makers, Vietnam was always put in the context of some larger abstraction: containment and dominos, which were all directly linked to a Russian threat to American security.

Despite Eisenhower’s penchant for sweeping doctrines like “containment” and “massive retaliation” and even the “domino theory” (a phrase which he popularized and introduced into American discourse), Eisenhower was acutely aware of the dangers of indiscriminate interventionism and over-extension. At the outset of his administration he endorsed a security strategy which prioritized defense of the homeland over expansive overseas interventions, and tight control over military spending.[4] It is worth remembering that Eisenhower rejected the option of military intervention to salvage the French position in Indochina in 1954.[5]

The idea that the conflict in Vietnam was a localized problem that was not instigated by Russia, or China was hard for Americans to grasp in the 1950s and early 1960s, because so little was known about that country. It would have been more accurate to view the situation in Vietnam as one of the last gasps of a fading era of colonialism, and the consequence of a botched process of decolonization than as the opening gambit in a wave of Wars of National Liberation newly launched by the Soviet Union to destabilize the sphere of American hegemony, as Kennedy believed. As the Prussian authority on strategy, Carl von Clausewitz famously observed “the first, the supreme, the most far reaching act of judgment that the statesman and commander have to make is to establish the kind of war on which they are embarking, neither mistaking it for, nor trying to turn it into something that is alien to its nature. This is the first of all strategic questions and the most comprehensive.”

By ignoring the internal civil war aspect of the Vietnam Conflict that derived from the colonial struggle, the United States failed to grasp the underlying dynamics of that conflict and thus did not pose the key question, whether this conflict could be resolved by American power at a cost that would not destabilize America’s larger global interests. If this was seen as merely a contest between two sides in a remote civil war, the answer would certainly have been no, but that question was rarely asked. To the extent that Vietnam attracted the attention of Washington, it was as a global Cold War problem. From the beginning, the Vietnam War was not about Vietnam, but always about some larger global abstraction. Small wonder that, it took so long for Americans to view Vietnam as a “country, not a war.”

As a result of nearly a decade of direct exposure to Vietnam, I began to understand the internal dynamics and the origins of the conflict in a quite different way from the superficial Gospel of National Security view of a small but crucial pawn on the global chessboard. Over time I began to question and then reject much of the Cold War baggage of the Gospel of National Security because of its flawed application to Vietnam and later to Iraq and the mindless interventions of the Bush-Cheney-neocon era.

But the advent of Donald Trump illustrates the costs of throwing out the baby with the bath water. After all, the Gospel of National Security was an outgrowth of the lessons of Munich and World War II about the indispensability of alliances, the link between authoritarian regimes and aggression, and the fact that in some cases, failing to responding to aggression because it was only about “a quarrel in a far-away country between people of whom we know nothing,” (as Neville Chamberlain said about the German occupation of the Sudetenland) can lead to calamity. Actually Chamberlain made the reverse error of defining a case of clear-cut aggression as a remote civil war, whereas Vietnam was viewed in Washington not as a civil war but as a case of external aggression. Before applying blanket concepts like the domino theory, it is crucial to understand the internal as well as the external context. Like most American’s in the early 1960s, I knew next to nothing about Vietnam or its history.

First Glimpses of “Vietnam”

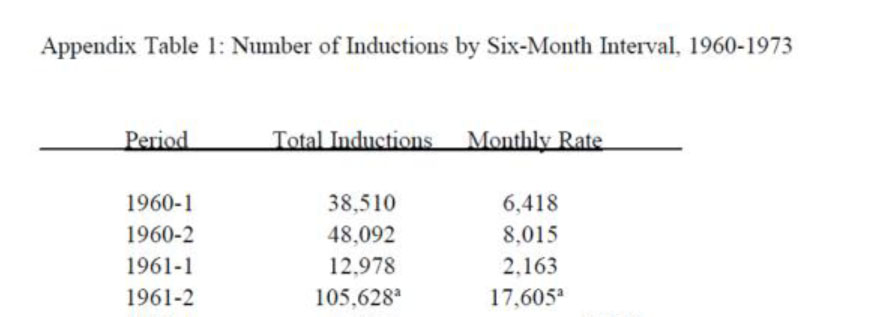

Although I wasn’t aware of it at the time, the first time Vietnam intruded on my consciousness was in the late 1940s as a result of the “Tonkinese” who featured in the musical South Pacific. Although I never saw the theatrical production, I played the 78 rpm album of the music constantly, and knew the songs by heart. Because I had not seen the play, I didn’t know that the actors portraying the two main Vietnamese characters in the original Broadway version were not Vietnamese, or even Asian, however. Liat, was played by Betty St. John, a Caucasian from Hawthorne, California, and her mother “Bloody Mary” by Juanita Hall, born in Keyport, New Jersey, whose father was African-American and whose mother was Irish-American. For America of the late 1940s that was close enough to portray “the Other” for theatrical purposes.

Betta St. John as Liat in the 1949 stage production of South Pacific – France Nuyen pantomines “Happy Talk” in the 1958 film of South Pacific

The original character of Liat in James Michener’s short story “Fo’ Dolla” in his Tales of the South Pacific is presented as “an educated woman who speaks fluent French.”[6] In the 1949 stage version and the 1958 film, Liat’s spoken lines are reduced to a few snippets of pidgin French. Her primary moment of (non-physical) communication with Lt. Cable is a pantomime of Bloody Mary’s “Happy Talk” with finger gestures, a decision by director Joshua Logan, replacing the original stage direction by Hammerstein “Liat now performs a gentle childish dance.”[7] Although the actress playing Liat in the movie version of South Pacific had native fluency in French, the pantomime was retained.

As Andrea Most writes, “Liat embodies the classic stereotype of the exotic Oriental woman. Rogers and Hammerstein were aware that they were dabbling in cliché as they worked on the script: ‘The more we talked about the plot, the more it dawned on us that onstage it would look like just another variation of Madama Butterfly.’ According to Rogers, the solution that they arrived at was not to develop Liat’s character further, but to add the story of Emile and Nellie. The addition of a complex and successful love story between two white people, however, only serves to heighten the formulaic and stereotypical structure of the former one.”[8]

Thus the first widely circulated image of a Vietnamese in America, which came on the scene at an impressionable time in my life, was a highly stereotyped portrayal of people without much of a voice, or really any context, since they were immigrants in a foreign land. Of course I had no understanding of what the term “Tonkinese,” the French colonial term for North Vietnamese, meant, or that they were really supposed to depict Vietnamese. The setting of the play in New Caledonia, following the Michener version, did not make the Vietnamese connection obvious. “Liat” was not only not a Vietnamese name, but was made up without reference to any particular Asian nationality. At least Hollywood, perhaps reflecting the heightened visibility of Vietnam after Dien Bien Phu, cast a mixed-race Vietnamese in the 1958 movie version of South Pacific (France Nguyen, who lived in France and whose mother was a French Roma or gypsy, discovered that Vietnamese names were too hard for Westerners to pronounce, and so adopted the given name “France” (her Vietnamese name was “Nga”) and dropped the “g” from Nguyen, and reversed the order of first and last names to conform with Western practice.

Current critical fashion interprets South Pacific not as a progressive and enlightened critique of racism that was ahead of its time, but as a clever rationalization for neo-imperialism. A particularly egregious example is the following argument that the apparently progressive message against racial prejudice is merely a feel-good cover for exploitation of Third World people and a justification of neo-colonialism and American imperial expansion.

“In light of all this rationalization, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s distinctly relativist justification of American expansionism in South Pacific makes sense. As Lovensheimer points out, in the same way that other Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals such as “The King and I and The Flower Drum Song helped to structure metaphors of containment in our dealings with non-westerners,” South Pacific in particular, reinforced post war expansionism and demonstrated an increasing acceptance of US global power. ….Also typical of the Orientalist narrative is the strange, exotic, ‘other’ character, a description that fits Liat perfectly. She represents the colonial male’s vision of the ideal female—a submissive, accessible woman, in need of domination by both her mother and Lt. Cable. Listening to the lyrics of “Younger Than Springtime,” we are reminded of the implicit meaning Rodgers embedded within this deeply romantic song:

My eyes look down at your lovely face/

And I hold the world/

In my embrace.

Heaven and Earth you are to me,

And when your youth and joy invade my arms.”

(5-7, 13-14. Emphasis added) 208

Their love is a metaphor for US imperialism—ownership over land. Notice, her youth and joy “invades his arms,” as if to say he didn’t have a choice. She was so beautiful he was forced to take ownership of her. Rodgers and Hammerstein’s simplification and almost complete silencing of Liat (who converses at length with Cable in Tales of the South Pacific) is a problematic aspect of the musical. It demonstrates what Christina Klein, English professor at Boston College, dubs “the infantilization of racialized others.”209 Although her character is central to the show’s thematic conflict, she utters only five short lines, each consisting of one to three words. Her “infantilization” and dependence on Cable vindicates America’s emerging role in South East Asia by arguing that in colonizing islands such as Bali Ha’i, America is in fact lending those who live there much needed fostering and support. Perhaps the most overt message of all is embedded in Bloody Mary’s efforts to entice Cable to come to the exotic island of Bali Ha’i:

Cable: Bali Ha’i… what does that mean?

Bloody Mary: Bali Ha’i mean… I am your island…mean…here am I,

Your special island. Come to me…come to me.

(Emphasis added)

The not so subtle implication here is that Bali Ha’i rightfully belongs to Cable, as a white American man, or more broadly, to white America. Thus, annexing it is simply fulfilling America’s divine destiny, ‘white man’s burden’ as bringers of democracy to the world.”[9]

Simpleton that I was at age ten, I was unable to read between the lines and grasp Rogers and Hammerstein’s subliminal call to arms to extend American rule into Asia in this paean to Empire, but only saw the anti-racism message, which did leave a lasting impression on me.

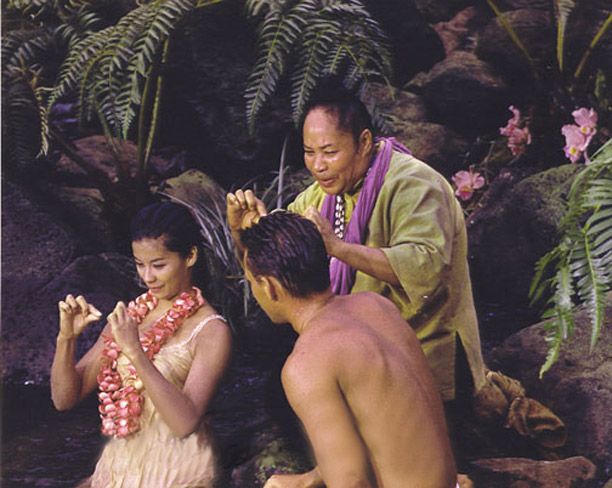

The subject of inter-racial liaisons, like Liat and Lt. Cable, was very sensitive in the late 1940s, and Oscar Hammerstein was quite bold in reinforcing the drama with the song “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught” which was a head-on condemnation of racism. I recall that my father was disapproving of “you’ve got to be carefully taught” though he seemed to be upset more by the idea that one should disregard the bonds of family and pride in ancestry rather than the racial issue per se. He had no problem with the marriage of Michael Lindsay, the son of his revered mentor at Oxford, who lived with us for a time and was almost a member of the family. While in China in the late 1930s Michael was in Peking inaugurating an Oxford-style tutorial program, when he met his future wife Hsiao-li. They fled to Yenan just ahead of the Japanese occupiers who had come to arrest them at Beijing University, and spent the war in close proximity to Mao, as described by Hsiao-li Lindsay in her fascinating memoir.[10]

Michael and Hsiao-li Lindsay at wedding – Michael Lindsay as radio operator for Mao’s Eighth Route Army in Yenan

My father cherished the couple and clearly had no problems with the inter-racial dimension of their marriage. Still, inter-racial marriages were not only sensitive at the time South Pacific appeared in 1948, they were illegal in many states, including Virginia, until the prohibition was overturned by the Supreme Court in Loving v. Virginia in 1967, although I wasn’t aware of this until much later.

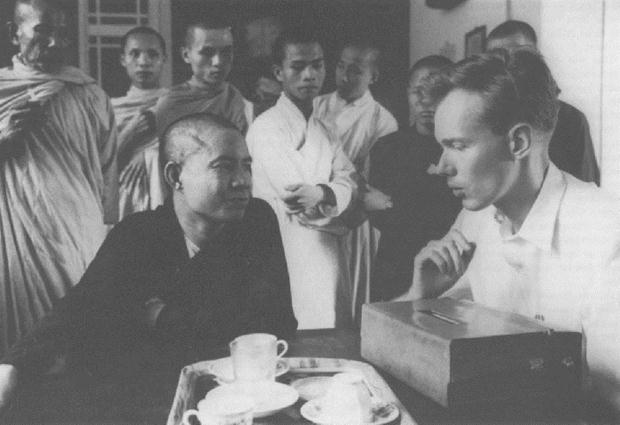

I was vaguely aware of Dien Bien Phu, but at the time it was just another Cold War crisis in a remote place. Probably the first direct impression made on me by a Vietnamese was as a student at Yale, occasionally glimpsing a Buddhist monk (I later learned that it was Thich Quang Lien who became an important figure in the Buddhist opposition movement) walking down Elm street in his colorful robes sometime in the late 1950s – a rare exotic presence in drab New Haven.[11]

Thich Quang Lien, as a member of the Committee for the Protection of Buddhism, being interviewed by Malcolm Browne, 1963(?)[12]

Unfortunately Yale did not prepare me well for my future encounters with Vietnam. Although I wasn’t especially focused on Asia (when my attention was focused abroad it was often to Latin America, as a consequence of my roommates from Cuba (Luis Mestre, son of the head of Cuban television in the Batista era, was especially affected), Columbia, and Venezuela. I took several courses which introduced me to the Asian region, none of which prepared me for the dramatic transformation that was already underway and would accelerate in the near future. The course on modern China was taught by David Nelson Rowe, the most reactionary China expert at a major university in the 1950s, whose wholesale rejection of the Maoist revolution and stalwart defense of Taiwan was reflective of the McCarthy era. He did not offer a very penetrating view of the sweeping changes that were transforming Asia. The nothing-but-the-facts course on Modern Japan and Asia by Chitoshi Yanaga likewise did not indicate the depth and extent of the forces of change at work in the region. I audited the course on Buddhism in Asia taught by Richard Gard, who later became the CIA expert on Buddhism in Vietnam and Southeast Asia. He focused entirely on the general philosophical tenets of Buddhism, and had nothing to say about the sociological or political aspects of Buddhism in Asia, let alone Vietnam.

Although I feel that Yale had failed to prepare me to understand the sweeping transformations I was about to witness at first hand, part of the fault lay in my own failure to seek out the extraordinary resources it offered, but which did not have a high campus profile. Unknown to me at the time, Paul Mus, the leading Western authority on Vietnam was at Yale during much of my time there. Since I had no special interest in Asia (my major was modern European history) I was unaware of this at the time. Nor was I aware of Karl Pelzer, a specialist on land use and demographics who was director of the Southeast Program at Yale for many years. His daughter, Christine Pelzer White was a fellow graduate student at Cornell, and an authority on land reform in Vietnam. Still, the “winds of change” blowing in Asia and the colonized world were not particularly apparent at the Yale of the late 1950s. This was in contrast to my direct exposure to the turmoil in Latin America through the personal experiences of my college roommates from Cuba, Venezuela, and Colombia.

Graduate School: Take One

My life’s path took an accidental turn toward Vietnam not long after my graduation from Yale. Despite a dismal undergraduate academic record (I spent most of my time with various singing groups while in college), I got a second chance, thanks to my father’s personal connection with the President of the University of Virginia. I was granted probationary admission to UVA, conditional on maintaining a good academic record, and enrolled in the Woodrow Wilson School of Foreign Affairs (which, at the time, had been detached from the Political Science Department, and focused on international relations, offering much the same curriculum as the School of Advanced International Studies of Johns Hopkins and Georgetown’s School of Foreign Service).

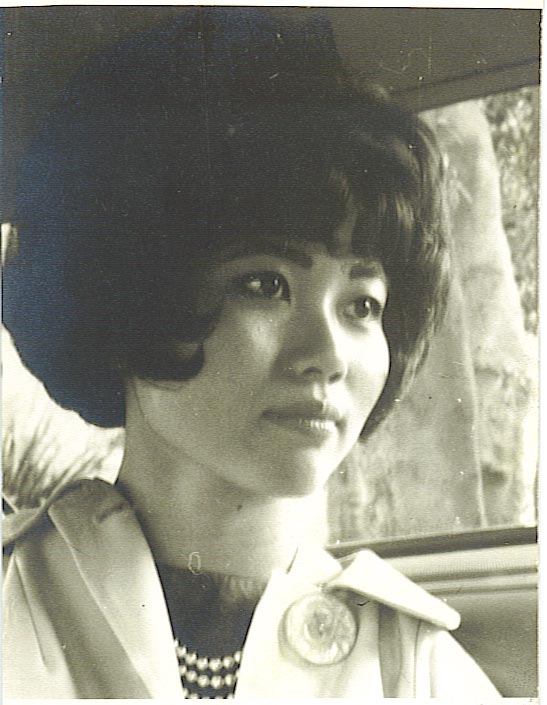

By this time I had decided to aim for a career in the foreign service. With this focus, and without the distractions of Yale singing groups, my academic record was strong and I was admitted into the graduate program with the goal of obtaining an M.A. degree. UVA was pivotal in my life for several reasons. First it gave me the academic credentials I would later need for admission into Cornell, where I subsequently immersed myself in studies on Vietnam, China, and Southeast Asia and obtained a Ph.d – the requisite “union card” to obtain a college teaching position. Even more importantly, by happenstance my UVA connections resulted in meeting Dương Vân Mai, my future wife and the joy of my life for over a half century. This, of course, was also a key aspect of my lifelong concern with and education about Vietnam.

The unwitting link in this connection was my fellow UVA graduate student and life-long friend Nguyễn Mạnh Hùng who, along with another close friend Tạ Văn Tài, as well as Nguyễn Tiến Hưng (later President Thieu’s economic advisor in the final years of the South Vietnamese Government), were among the first wave of Vietnamese to come to the United States for study as the American involvement in Vietnam began to intensify. At the time I had no ear for Vietnamese tones, and found it impossible to differentiate between Hùng

and Hưng,

though fortunately the problem was resolved by Nguyẽn Tiến Hưng adopting the American name “Gregory.”

In December 1961, Hùng invited me to Washington to attend the Christmas party given by the South Vietnamese Embassy – at the time presided over by Trần Văn Chương, the father of the soon-to-become infamous Madame Ngô Đình Nhu. Since our shared tastes in music and interest in the guitar was one of the things that had brought Hùng and I together, he persuaded me to bring my guitar and sing a song at the reception. It was during the course of that evening that I met Mai, an encounter which she has described in her beautifully written memoir and family history Sacred Willow. For me it was love at first sight, and the relationship deepened over the remainder of my stay at UVA, despite the commute that was necessitated by the distance between Charlottesville and D.C.

Mai at Vietnamese Embassy Christmas Party, Washington D.C., December 1961 – Mai at Georgetown 1961

Fortunately for me, Mai’s given name did not involve any complex phonetics or tones. I could not distinguish between her middle name “Vân” (Cloud) and “Văn” (“literary” or “scholar”) the widely used middle name for men only. Her family name, Dương, was a challenge. Although after some explanation I was able to grasp that the “D” without a bar through the upright stroke meant “Z” (in North Vietnamese pronunciation), the succeeding vowel sounds (“ươ”) were beyond my capacity. The ultimate challenge for a foreigner attempting to learn Vietnamese is to pronounce words containing the vowel combination “ươ” when the further hurdle of a half-glottal stop (dấu ngã) –which features an aspirated break as in “uh-oh” in a single vowel) was added. Much later I devised a nonsensical tongue-twister to underline the point: “tôi ưỡn ngực ra một cách kỹ lưỡng tại Nữu Ứơc” (“I carefully thrust my chest out in New York”) – to the amusement of some of Mai’s relatives, who had never had to think about the issues this combination of vowels and exotic tones might pose for a foreigner. Ask a native speaker of Northern Vietnamese dialect to repeat the phrase fast three times. Or listen the following Google Translate clip. Even the automated synthetic voice seems to run out of steam by the end of the phrase and can barely make it through.

Later attempts to learn the lyrics to a Vietnamese song I liked, “Gởi Gío Cho Mây Ngàn Bay” (untranslatable, roughly “I send the wind to make the thousand clouds float by”) the complex tones and phonetic vowels involved had me stumped. I later found out that this literal “tone-deafness” could be remedied with systematic study and a musical ear, but it did underline the point that the price of the most basic aspect of cross cultural understanding, language fluency, would be very high.

In my second year of graduate study at UVA (1961-62) I concluded that since obtaining a Master’s degree would require the same amount of coursework as a Ph.d., with only a longer and more demanding thesis separating the two, I might as well try for the Ph.d, which would require only a year or two of additional effort. At the time I did not contemplate an academic career, but thought it would be a useful credential in any case. So as I completed two years of coursework, I enrolled in the Ph.d program, passed five of the six required preliminary exams in various aspects of international relations (and was preparing to take the sixth), and language exams in French and German (the latter with considerable difficulty), and was about to confront the major task of selecting a thesis topic. I had done a lot of course work on Latin America, and had even taken a semester of Portuguese at Harvard Summer School, as a result of a growing interest in Brazil, which was emerging on the scene as a significant player in South America at the time. However, I did not speak Spanish and had barely begun the study of Portuguese, so that pursuing that path would have considerably lengthened the process of pursuing a Ph.d at UVA.

Facing the Draft

At this critical juncture, fate intervened. My draft board (still in Massachusetts, though I had been living mostly in Virginia for a number of years), informed me that my educational deferment from the draft would soon end. To this day I don’t know for sure why enrolment in good standing in graduate school did not ensure an automatic deferment from the draft, as it did for a generation following me who successfully avoided military service. I vaguely remember taking a test of some kind under government auspices, and doing miserably on the math portion, which was half the test. I had acquired a math phobia in sixth grade as a result of a disastrous teacher and was now paying the price. An article about the draft following the tightening up of exemptions in 1967 described the earlier period as one where the average draft age was 22 (I was 23 when I received my draft notice). There evidently was a test required for maintaining exempt status, though generally remaining in good academic standing in a full time course of studies was sufficient.[13] But if the 1967 standard was in effect in 1962, I would have had a maximum two years to complete a masters degree, and by spring 1962 my time was up.[14] As far as graduate school exemption was concerned, the new 1967 standard was probably similar to that in effect in the early 1960s. “Those with one year toward a master’s degree will be deferred for one more year to get their degrees. Those with one year toward a Ph.D. will be deferred up to four more years to get that degree.” [15] I had passed five of six qualifying exams for the Ph.d program, but had not yet been formally admitted to it. So probably I had simply run out of time as far as the draft board was concerned. It could have been that my Massachusetts draft board was mainly concerned about my eluding their grasp by moving to Virginia.

The probable main cause of my draft notice, however, was the Berlin crisis set in motion by the building of the Wall which commenced in mid-August 1961. Kennedy interpreted this as a challenge to his personal leadership following his disastrous summit with Khrushchev in June 1961, and ordered a dramatic increase in military strength to send a message to the Russians. This, in turn, required a substantial escalation of the draft quotas in 1962. Thus my conscription in the Army was mainly caused by an escalation of Cold War tensions which marked the first phase of my encounter with Vietnam.

A study of the Vietnam-era draft notes that “President John F. Kennedy, who began the escalation of the American military presence in Vietnam, also defended the peacetime draft and the Selective Service in 1962 statement, stating that ‘I cannot think of any branch of our government in the last two decades where there have been so few complaints about inequity.’ One year later, the Pentagon acknowledged the usefulness of conscription, because one-third of enlisted soldiers and two-fifths of officers “would not have entered the service if not for the draft as a motivator.” The Selective Service authorized deferments for men who planned to study for careers labeled as ‘vital’ to national security interests, such as physics and engineering, which exacerbated the racial and socioeconomic inequalities of the Vietnam-era draft. Of the 2.5 million enlisted men who served during Vietnam, 80 percent came from poor or working-class families, and the same ratio only had a high school education. According to Christian Appy in Working-Class War, ‘most of the Americans who fought in Vietnam were powerless, working-class teenagers sent to fight an undeclared war by presidents for whom they were not even eligible to vote.’”[17] Of course there was no anti-war movement to speak of on American campuses in 1962 prior to the direct combat involvement of American troops in Vietnam – certainly not at conservative UVA – and the concept of draft evasion, let alone resistance was not on the radar of the vast majority of draft-aged males. I certainly did not fit the profile of a “powerless, working-class teenager.” But, as I soon discovered, even in a highly selective cohort like students at the Army Language School, the number of college graduates induced to volunteer by the threat of being drafted was quite small. As far as I know, I was the only private who had done graduate study among the hundreds of very bright enlistees, many of whom had come straight from high school.

Whatever the case, I was now faced with the choice of submitting to the draft for a two year term of service, probably ending up as a clerk-typist at some military base, or volunteering for three years in the hope that I would be able to spend my time in the military more profitably, even at the expense of an additional year. My older brother Charles had gone to the Army Language School in Monterey, California for a year and became fluent in Russian. He was stationed in Germany and spent a pleasant year using his generous leaves to travel all around Europe on a shoestring budget. The thought occurred to me that I might be able to study Portuguese at Monterey, so I decided to enlist. As it turns out I don’t think the Army even offered Portuguese language training.[18]

The only route to language school was as an enlisted man (e.g. not an officer) who had been admitted into the Army Security Agency, the military arm of the National Security Agency which dealt with code-breaking and signals intelligence, prior to actually being inducted. This, in turn, required an extensive security vetting which was required for receiving a cryptographic security clearance, which was a level above Top Secret. Given the sensitivity of maintaining secrecy about codes, sources and methods of intercepted communications, ASA placed great emphasis on this cryptographic clearance, which was to play major role in my army career later on.

In addition to being accepted into the Army Security Agency, it was necessary to pass a language aptitude test to get into the Language School. This was essentially a test of symbolic logic. The questions were based on a made-up language somewhat similar to Esperanto, and required manipulation of a set of Esperanto-like vocabulary words using patterns of syntax specified in the examination. This kind of symbolic logic was akin to mathematics. Because of my math phobia I automatically tuned out every time I encountered a math-like task. Fortunately I barely squeaked through with the minimum acceptable score. I later discovered that the people in my Vietnamese class at Monterey who scored the highest on the language aptitude test had the most difficulty learning Vietnamese, which had a fairly simply grammatical structure, but was fiendishly difficult in terms of pronunciation. Because of Mai, I listed Vietnam as my fifth preference, though I was aiming for Portuguese, and if not, Spanish, French or German. Since I was the probably the only applicant who even had Vietnamese on his list of preferences, naturally I was assigned to study Vietnamese. But first, I had to complete basic training.

From Fort Jackson to Monterey

My army career was launched in Fort Jackson, South Carolina. I arrived by train with a small group of new recruits from Virginia on June 18, 1962. We were immediately lined up and marched to the barber shop where everyone was shorn like sheep – not as traumatic an experience for most in this pre-“long hair hippy” era as it would be for the next generation of recruits. Next stop was an assembly area where a now large group of recruits would be given instructions on what to do next. An imposing black sergeant in creased fatigues stared contemptuously down on us from a slightly raised platform. In time honored Army fashion, he scanned the audience to find the most hapless target which he would ridicule to intimidate and establish his authority, as well as the insignificance of recruits in general. He zeroed in on a carrot-topped, bespectacled lost soul in the fourth or fifth row of the group seated on the ground below the platform. Leaning over in a mock-solicitous posture, he asked, “Boy, what’s you favorite flower?” The defenseless target immediately became an object of ridicule, but it also underlined that the sergeant could victimize anyone he chose, and manipulate group pressure at will. Although I was certainly aware of the racial overtones of this incident, I didn’t think much about it at the time. In retrospect I imagine that this scene must have had an impact on the many Southern white boys who had, as of 1962, never experienced having to be deferential to a dominating black authority figure.

We lived in World War II era barracks, with facing rows of ten double-decker bunks. There was one other college grad in my platoon, the rest were all southern farm boys, with the exception of one inner-city black kid from Baltimore, whose improbable (especially for that time and place) buddy-buddy relationship with a young white country boy amused the entire outfit. The only other black in my training company of about 120 was one of the handful of college graduates, and had been captain of the football team at University of Cincinnati. A red-neck living in his barracks made the mistake of trying to harass him in the presence of a large crowd. The burly football player simply picked him up and hurled him against the barrack walls, where the redneck collapsed in a heap. Following this incident, which happened early on in our training, there were no further racial incidents in Company B. Perhaps the situation would have been different in the town of Columbia, adjacent to the base, but even there the times were changing.

“The 1940s saw the beginning of efforts to reverse Jim Crow laws and racial discrimination in Columbia. In 1945, a federal judge ruled that the city’s black teachers were entitled to equal pay to that of their white counterparts. However, in years following, the state attempted to strip many blacks of their teaching credentials. Other issues in which the blacks of the city sought equality concerned voting rights and segregation (particularly regarding public schools). On August 21, 1962, eight downtown chain stores served blacks at their lunch counters for the first time. The University of South Carolina admitted its first black students in 1963; around the same time, many vestiges of segregation began to disappear from the city, blacks attained membership on various municipal boards and commissions, and a non-discriminatory hiring policy was adopted by the city. These and other such signs of racial progress helped earn the city the 1964 All-America City Award for the second time (the first being in 1951), and a 1965 article in Newsweek magazine lauded Columbia as a city that had “liberated itself from the plague of doctrinal apartheid.”[19] Because the military had been at the cutting age of desegregation since the 1950s, the dominant presence of a large military base next to Columbia must have been a factor.

We were under the constant supervision of First Sergeant Mullins and Staff Sergeant Barnes, a Native American veteran of the Korean War. Unlike some of the more mellow basic training centers, like Fort Dix (New Jersey), and Fort Ord (California), Fort Jackson was a hell-hole in the summer, with suffocating heat and humidity and, like other Southern military training bases such as Fort Leonard Wood (Missouri), was known for its grueling training regime. The basic idea was to reduce the trainees to automatons who would execute any order without protest or hesitation. The first step was to physically wear down the trainees by sleep deprivation and constant marching to ensure that no one had any reserves of energy to offer any resistance and simply went with the flow because it was the only way to survive.

Somehow I did manage to survive, scoring a “sharpshooter” rating on the rifle range in the process, as well as crawling under barbed wire with live machine gun fire whizzing overhead.

Infiltration course with live machine gun fire. Ft. Jackson, South Carolina, 1962.[20]

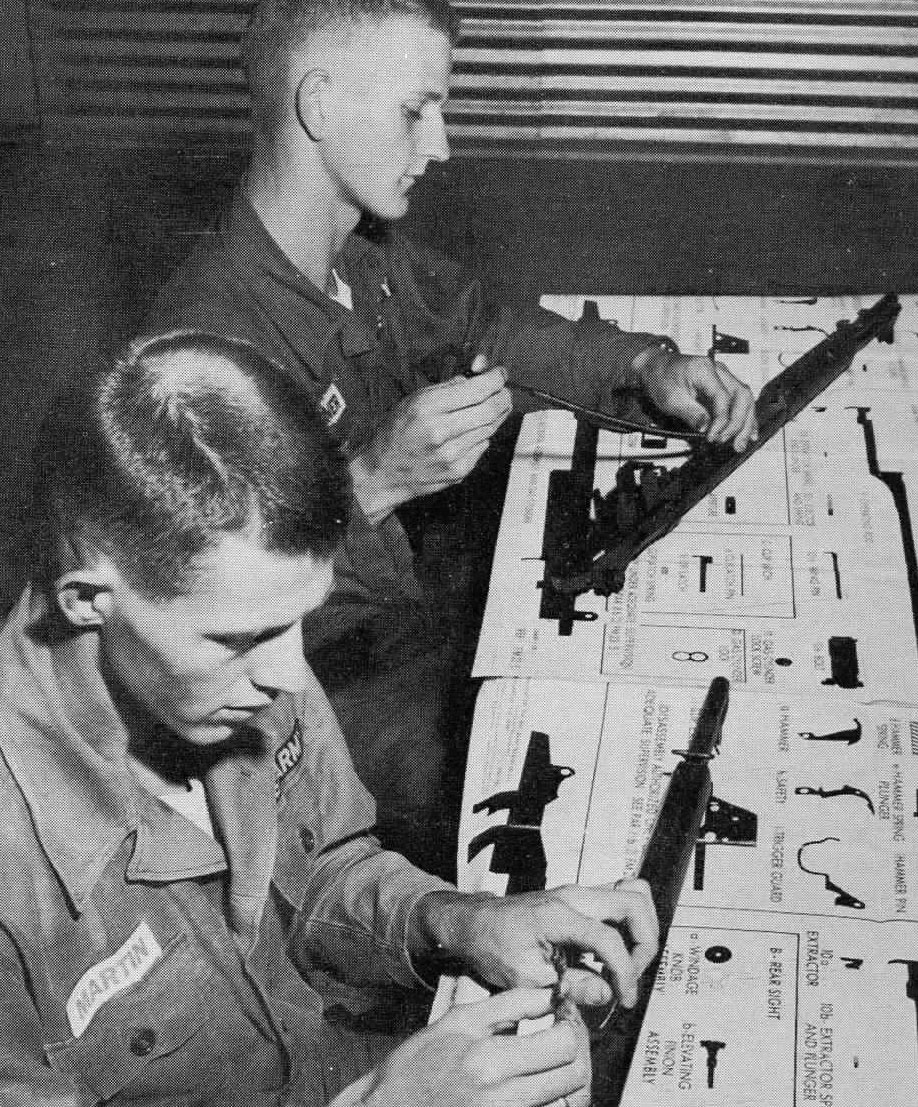

We survived being herded into an enclosed building filled with tear gas (to make us understand why it was a good idea to carry a gas mask at all times). We sat through mind numbing courses of instruction on topics like assembling and disassembling the M1 rifle. We were still training with this World War II relic because the M16 had not yet been adopted by the Army. Army instruction was based on the idea that the only way to communicate to large numbers of recruits with vastly different backgrounds and aptitudes was to devise an idiot-proof protocol that would be parroted by the instructor. Unfortunately this did not work at either end of the educational scale. For me, the mind-numbing jargon (“grasping the barrel and receiver group between the thumb and index finger, rotate at a 45 degree angle”)[21] simply triggered a mental fade out. I, as well as the farm boys would have caught on much quicker if the instructor had simply said “jus’ grab this here doo-hickey, and give it a good yank…”). For me, a teacher in later life, this was an indelible negative lesson in pedagogy.

“Grasp the barrel and receiver group between the thumb and forefinger” – rifle disassembly instruction at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, 1962.[22]

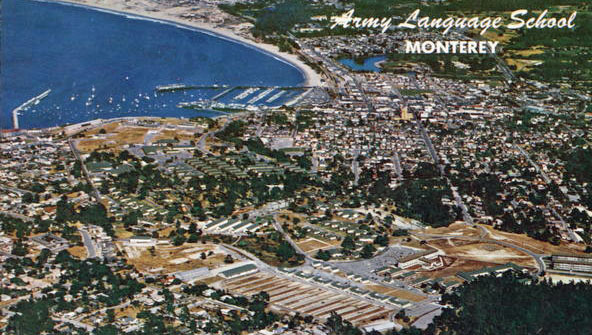

The purpose of basic training, however, was not simply to instruct, but also to socialize civilians into a new culture of automatic compliance. For those that were slated for the infantry, a much more extensive advanced infantry training course provided the necessary training and skills. In my case, it was just an interlude between induction and my real training, a 47 week training course in Vietnamese at Monterey in the Army Language School (which was transformed into a joint-service institution by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara in 1963, and the Monterey campus was renamed the Defense Language Institute, West Coast Branch).

I arrived in Monterey in September 1962. Students from the older language training groups like Russian were housed on the lower part of the base in old World War II barracks, while students in Asian languages were housed in newer permanent barracks, not unlike a college dormitory, two to a room. It was situated at the top of the hill overlooking Monterey bay. Every morning we would fall out for reveille at 6 a.m. and form in ranks in the mist for roll-call, enjoying the spectacular view of the ocean at dawn.

Monterey was once even more of a country club. I later learned from people who had been there in the 1950s that students were more or less left to their own devices as long as they showed up in class and kept up with their training. Some even rented apartments in neighboring Carmel and commuted to the base.

Things had tightened up somewhat when I arrived – no more living off base. Moreover, since Monterey was now a joint service facility, we were mixed in with Marines and Navy personnel. All the Marines were at least lance corporals and, having seniority over us Army privates, were put in charge of the barracks. That was the final blow to the 1950s country club atmosphere of the old Army Language School. Still, their authority was limited to ensuring that our rooms were squared away, our tile floors waxed and buffed daily (the one electric buffer on our floor was in constant demand), and that we showed up on time at reveille.

Due to a clerical error, my name did not appear on the duty roster, so I never had to do KP (much to the irritation of a few fellow students who learned of my good luck), the only military task required of us, other than buffing our floors in preparation for inspection, and the morning assembly. The actual language training was relentless. There were four intakes of new students each year. In the case of Vietnamese, my September 1962 intake consisted of 27 enlisted men and officers, divided into three classes. One class consisted entirely of officers. One had a mix of privates and non-commissioned officers (sergeants), and my section of nine consisted entirely of newly inducted privates, all ASA enlistees. Spending six hours a day in class performing repetitive tasks with the same people, in the same room, every weekday, for nearly a year, can be trying at times. However, it did achieve the Army’s objective. Everyone graduated in 47 weeks with at least a rudimentary fluency in Vietnamese. You couldn’t not learn it with that relentless exposure. One student in our class was basically a neo-Nazi with a racist contempt for Vietnam and Vietnamese. He sat sullenly through the hundreds of hours of instruction, trying to block it out of his ears. But even he absorbed enough of the language despite his passive resistance to pass the final exam at the end of the course.

For the enlisted men, who were almost all in ASA, achieving fluency in the language was critical, because they had to be capable of interpreting and understanding enemy communications. For the officers, it was merely a tool, a means to an end, since most of them would be military advisors. It was a way to facilitate doing their job, while for us it would be our job. By and large, the officers, most in middle age, had less aptitude for language, and few of them were able to cope with the demanding tonal aspects of Vietnamese.

One of the most memorable examples of this was Col. Francis W. Dawson. As a young lieutenant, Dawson had been the first to scale the sheer cliffs of Pointe du Hoc at Normandy in June 1944, to lead the successful assault on the German artillery position overlooking the landing beaches of the D-Day invasion.[23]

Lt. Francis W. Dawson

This was one of the most iconic moments of the greatest war in American history, and Col. Dawson was an authentic American hero.[24] But at Monterey, his language skills were another matter. Col. Dawson was a genial “good ‘ol boy” from South Carolina with a thick Southern accent. He was totally unable to produce anything which resembled a Vietnamese tone (there are six, and the language is unintelligible unless the tones are accurately rendered).

Although awed by his historical accomplishment and connection to what was not yet called The Greatest Generation but was highly respected by those of us who followed in their footsteps, we snarky enlisted men could barely contain ourselves listening to Col. Dawson’s loud and effusive morning greeting to Nguyễn Đức Hiệp the venerable chair of the Vietnamese language department, a frail gentleman with a wispy Confucian beard. “Chao Ông Hiếp!” he would bellow good naturedly. Mr. Hiệp would accept it in good humor, though he must have cringed inwardly at being called “Mr. Rapist” rather than “Mr. Harmony” due to Col. Dawson’s ebullient transformation of a falling tone to a rising tone – ironically the only tone he was able to reproduce.

It was only much later that it occurred to me that Col. Dawson was a perfect illustration of the fact that the qualities that led to victory in World War II were not the qualities that would lead to success in Vietnam. Personal heroism framed by brilliant grand strategy, backed by overwhelming firepower and America’s industrial might was decisive in D-Day, but what was needed in Vietnam was a sensitive understanding of both the big picture, including a grasp of the constraints on American power in the era of decolonization, and the smaller picture, the absolute necessity of understanding Vietnamese culture and history, and recognizing that it was a country not just a war. Col. Dawson’s assignment was in Vietnam was to advise the Vietnamese Special Forces, but despite his own hard-earned martial skills I doubt that there was much he could teach his Vietnamese counterparts, who had been immersed in a complex fratricide for several decades, however great a warrior he had been on the cliffs of Pointe du Hoc.

The officers, with ferocious commitment to their professional duty, would stay up half the night to memorize the five pages of Vietnamese dialogue that each student was required to recite every morning. Rote memorization was a pedagogical technique long ago abandoned in the United States, but at the time still favored by the Monterey Vietnamese Language Department because of its cultural familiarity. By sheer force of will, the officers managed to reproduce a distant approximation of the sounds, though they were incomprehensible to the Vietnamese instructors. In deference to the officers’ military rank, the instructors stoically stood by without a word of correction during their recitations, knowing that the officers had with supreme effort done the best they could. But it was galling for the officers to observe the young enlisted men, most straight out of high school, breeze into the coffee shop in the morning and, in the amount of time it took to finish a cup of coffee, effortlessly commit their five pages of dialogue to memory just in time for class. (For me memorization took a lot longer, and I had to work hard at it every evening).

Breaks in the Routine

Our Monterey class commenced in September, 1962. After a few weeks we fell into the routine that was to continue for 47 weeks until we graduated. Our world consisted largely of small classroom in which eight of us sat in a horseshoe arrangement seated against the walls and performing the repetitive work of language acquisition. In mid-October, however, the outside world came crashing in on us as the Cuban Missile Crisis erupted. After class one day Eric Colby, (Ông Côn) who lived with his wife in a small army-supplied house at the bottom of the hill next to the rear entrance to the base, invited several of us to watch the scheduled October 22, 1962 address of President Kennedy on his TV (there was no common area with a TV in our barracks).

As we listened to Kennedy, the gravity of the situation became apparent to us. He said “It shall be the policy of this nation to regard any nuclear missile launched from Cuba against any nation in the Western Hemisphere as an attack on the United States, requiring a full retaliatory response upon the Soviet Union. …As a necessary military precaution, I have reinforced our base at Guantanamo, evacuated today the dependents of our personnel there, and ordered additional military units to be on a standby alert status.”[25]

We tried to figure out what the crisis would mean for our small detachment at Monterey – after all, we were in the Army and presumably would be affected in some way if war broke out. At the least, nearby Ft. Ord might be a target if there was an all-out nuclear exchange. JFK’s television address brought home to us the perils of the Cold War in a way that hadn’t occurred to us, as we initially luxuriated in what was for us a country-club routine, following the rigors of basic training. But the crisis came and went, life at Monterey proceeded on its own rhythms, and we mentally retreated back to the small world enclosed in our enclave at the top of the hill overlooking Monterey bay. Soon the routine became a grind.

After six months or so of the repetitive tedium of same faces-same routine our class of nine enlisted men was crawling up the wall with boredom. To relieve the tedium we invented ways to keep ourselves amused, not all of which were acceptable to our teachers. I started a trend by scouring the dictionary for offbeat Vietnamese phrases as a distraction. We all had Vietnamese names. Mine was Ông Ất. When Mai heard this she told me that was a name adopted only by peasants, rather than anything literary or refined. Instructors and students alike used the formal “Mr.” because even in a year long course learning the appropriate status pronouns for talking with superiors, equals, or subordinates was far too difficult, so the instructors settled on a artificial and impersonal “I” and “you” for every situation, including students and teachers.

One of the most challenging language learning tasks I encountered over the continuing process of attempting to master Vietnamese was learning the incredibly complex protocol for employing the multiple terms used in “I-you” forms of address, all of which required sophisticated knowledge of the complex fabric of Vietnamese social relations, often daunting even to a native speaker. (Dear Mother’s Younger Uncle, nephew would like to ask mother’s younger uncle if..” – not “I would like to ask you”). When a relationship was outside the familiar Vietnamese social structure, it required adaptation. When I later interacted with Vietnamese defectors, some older than I was and some younger, many of them used called me “captain” because it acknowledged that I was in a position of authority as far as they were concerned, and I seemed to be about the right age (it couldn’t be “colonel” because I wasn’t old enough). It also was a clever way to position me outside of the family based cultural network of terms of address, since I was not Vietnamese. And since there was no opposite term linked to captain (as “uncle” to “nephew”) they could use the impersonal “tôi” to refer to themselves, since they had already granted me superior status as “captain.”

At the beginning, my musical training was helpful in learning the contours of the six tones. One of the first phrases we learned was “Ông có cốc không?” (“do you have a glass?”). The first word was a neutral tone, followed by two rising tones, and ending with a neutral tone. One of the challenges was to learn what to do when confronted with successive rising tones (the first should be at a slightly lower pitch, leading into the next at slightly higher pitch, with the final word, a neutral tone, at a higher pitch than the initial neutral tone word because it follows two rising tones. Musically, it might be notated as

Ông có cốc không

As time went on, however, it became apparent that the pitches of Vietnamese tones depended entirely on the context (what preceded and followed) and the emotional intention of the speaker. I began to realize that English itself is a tonal language, with infinite rises and falls and subtle inflections which often baffle non-native speakers. The difference is that the rises and falls in English inflection are not systematized into tones. It took about three months to get beyond my sing-song approximation to become more fluid and improvisational in reproducing tones according to context – a learning process which continues to this day.

All our instructors were North Vietnamese with a Hanoi accent. They had left Vietnam in the 1950s and did not have a real grasp of life in South Vietnam, certainly not life as it was in 1962. Thus we did not learn much about the war from them. The first time we heard a Southern accent was about half way through the course, when the Vietnamese Department added an instructor who was from Tây Ninh, in recognition of the fact that most of us who would use the language (especially the advisors) would have to cope with it. When Miss Tây Ninh opened her mouth for the first time in our class, we spontaneously all roared with laughter, much to her consternation. For us, it was like hearing someone from rural Alabama for the first time, after being carefully taught the equivalent of Oxford English. The term that set us off was Bộ Quốc Gia Giáo Dục (Ministry of Education) which sounded to us something like Boh Woke Ya Yow Yook, rather than the Northern “Boh Kwoke Za Zow Zuk” The following synthetic combination of the words from Google Translate doesn’t capture the exact pitch and trajectory of the phrase, but it gives an idea.

the hard, abrupt North Vietnamese glottal stop (Bộ) in Southern dialect gently approaches the pitch floor and rebounds like a sponge off a mattress, rather hitting it hard with a definitive stop. The overall effect was of a rubbery and supple continuum of sound, characterized by all “Z” and “Gi” sounds becoming “Y”s. When I later moved to Mekong Delta I discovered that some Southern rural accents were even more distant from the formal Hanoi dialect that we were taught, and even after years of exposure, I never felt quite comfortable dealing with this variation of Vietnamese because Monterey-standard Northern dialect was imprinted in my brain.

Another example of the distinctive elasticity of Southern dialect was the way in which questions could be deflected by simply acknowledging the question without answering it. Mrs. Chất, my landlady in My Tho was a master of this art. When asked something she would rather side-step, she replied with a one-syllable response: “dạ.” When Northerners say this, it is a crisp and short polite way to respond to a question, especially when responding to a superior, with a sharp “zạ” which abruptly crashes into the vocal floor of the full glottal stop. It means “yes, I hear you” and is usually followed by a direct answer to the question. Sometimes “dạ” can by itself mean “yes” or “O.K.” But in conversing with Southerners, “dạ” can often be the quintessence of ambiguity.

Mrs. Chất’s characteristic response to questions was a long drawn-out “yaaaaaaaahhhhhhhhhhhhh” which starts out near the floor, but gradually ascends in a lazy upward trajectory over a period of perhaps five or six seconds, until it trails off into an indeterminate and inconclusive nothingness. It is like an English speaker reluctantly responding to an unwanted question with an equivocating “weelllll.” I subsequently adopted this as a way of evading spousal interrogations, much to Mai’s frustration (she is, after all, a northerner, and prefers a responsive and clear cut answer!).

There is a larger point to this discussion of what may seem to be merely linguistic trivia, which is that ability to communicate requires more than fluency in the formal language of the classroom. Language is a product of culture, and to be fully “fluent” it is necessary to understand the cultural underpinnings of the formal language. This is, in fact, the theme of the next chapter.

As the preceding intakes graduated, our September 1962 entry class attained seniority. I was selected to represent the Vietnamese language department in the orientation for new incoming students of all languages. The idea was that a speaker from each language taught at Monterey would say a brief phrase, to reassure the new students by showing them that mastering even the most exotic languages could be done. When it came my turn I said “Thay mặt Ban Sinh Ngữ Quân Đội, tôi chào mùng các bạn, và chúc các bạn sẽ gặt hái được nhiều kết qủa tốt đẹp trong niên học sắp tới.”(On behalf of the Vietnamese Department of the Army Language School I send you greetings and best wishes for achieving great results in the coming academic year.” I couldn’t have formulated this fancy language on my own at the time, and I think Mai must have suggested what I should say when I wrote her what my assignment would be.

At the time I was not really fluent in Vietnamese, but my ability to reproduce the sounds was good, and I had gotten beyond the mechanical sing-song imitation of tones to something approximating a conversational flow, and what I could say I was able to say more or less convincingly. Japanese and even Chinese sounded doable to most of the audience, but Vietnamese was another story. An audible collective gasp came from the audience, with the unmistakable implied question “You mean we’re supposed to learn stuff like THAT?”

Not only were the complex phonetic sounds of some Vietnamese vowels totally alien to an uninitiated auditor, and the tones (six of them, including full and semi glottal stops) far more difficult and complex than Mandarin Chinese, the only other tonal language represented, but to underline how weird the language was, I had inadvertently ended on a rising tone so that the phrase simply hung suspended in the air, rather than concluding with a falling pitch like most English sentences. It was like a musician hearing a dominant seventh chord, and waiting for the resolution to a tonic which never arrives. As I walked back to my place from center stage, it was clear the audience was perplexed and disoriented: they assumed that I wasn’t finished, and that more would follow.

Ken Woodward (Ông Khấn – Mr. Prayerful!), a nephew of the actress Joanne Woodward, and a boisterous rough and ready young man, was a handful for the reserved Vietnamese instructors. His Vietnamese was intelligible but the pronunciation was only approximate (he would pronounce “fog” (xương mù) as “here comes da soo-wung moo” he would say, looking out the window at the creeping Monterey mist, and feigning a gruff tough-guy New Joisey accent. I used to peruse the dictionary in search of offbeat tidbits. We used Nguyễn Đình Hoà’s Vietnamese-English dictionary which I believe was the only one available at that time. I discovered the phrase “nó có biết cóc gì đâu.” Nguyễn Đình Hoà’s decorous translation was “he doesn’t know beans,” but it might be roughly colloquially rendered “he doesn’t know sh-t.” The pronoun“nó” is considered particularly disrespectful, and used to address children, animals, criminals and foreigners. When an instructor would ask Ông Khấn a question, the rest of the class would chorus in unison “nó có biết cóc gì đâu!, implying that it was useless to ask Ken and the question should be directed to someone else. The instructors were shocked at the language we were using, which must have grated like sandpaper on them, in addition to being disrespectful. So we toned it down a notch and, without saying the exact words, would wordlessly hum a melody based on the tones of the phrase in chorus whenever Ken was asked a question.

My dictionary research also turned up another useful phrase, “biết thì thưa thốt, không biết, thì dựa cột mà nghe.” (The implied setting is private instruction in the home, with the student respectfully seated on the floor leaning against a pillar, while the teacher questions him/her). The injunction is “if you know the right answer, state it respectfully; if not, lean back against the pillar and listen” while the teacher enlightens you. In other words, respect the teacher by not trying to fake it or bluff your way through. Admit your ignorance and submit to being instructed by someone wiser than you. This was inevitably turned against Ken, who excelled in bluffing and responding to questions with wild stabs in the dark. “Xin Ông Khấn hãy dựa cột mà nghe!” (Mr. Khấn, kindly lean back against the pillar and listen,”) we all chorused in unison. Ken was a good sport about being the focus of our juvenile gibes, and he enjoyed these attempts to relieve the boredom as much as we did.

Sketchy Understanding of the Vietnam War in 1962-63.

Given everything that happened later in Vietnam, it may be hard for today’s reader to imagine a situation in which people were chomping at the bit to be assigned to Vietnam. But this was 1963 and the ferocity and futility of the war was not yet evident. In fact, it is remarkable how little attention was paid at Monterey to what was actually going on in the country. We did not watch TV, listened to music on the radio not news (fortunately my roommate Rich Hendel, a graphic artist and graduate of the Rhode Island School of Design was a classical music addict, and since he owned the only radio in our room, and my tastes were similar to his, that is what we listened to).

I didn’t pay much attention to the left-liberal KPFK commentary that was interspersed between music programs, but I’m sure their opposition to America’s support for Ngo Dinh Diem must have penetrated my consciousness in some way, but it was not yet a prominent issue and, in an case, was above my pay grade, so I dutifully continued to prepare myself for a Vietnam assignment. No newspapers were easily obtainable on base, and you would have to go downtown to buy Time or Newsweek, so we lived in somewhat of an information void. The Buddhist crisis of 1963 took place while I was still in my enclosed bubble in Monterey, and I certainly didn’t follow it, or any other news event, as closely as when I was an avid reader of the New York Times and Washington Post at UVA. And as noted, we didn’t have regular or easy access to a TV so I didn’t watch television news.

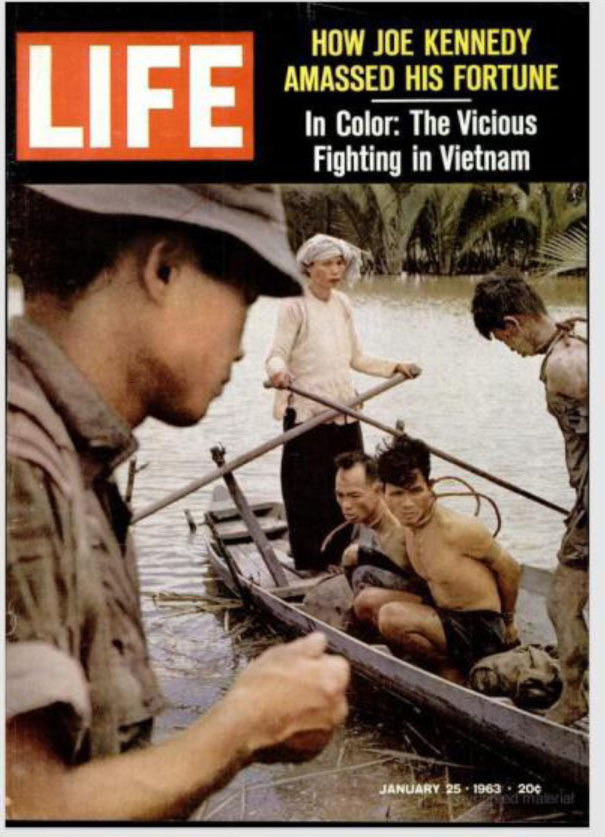

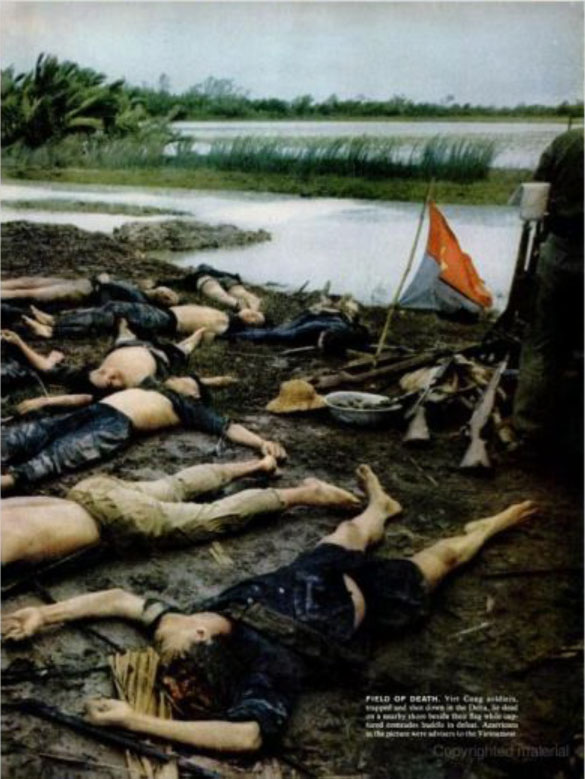

Occasionally I would walk down the steep hill to visit the bookstore downtown. It was probably there that a Life Magazine cover story on the Vietnam caught my eye. This was the first vivid graphic image of guerrilla warfare in Vietnam that I can recall. Prophetically it was about the war in the Mekong Delta, where I would later spend four years.

Life Magazine, January 25, 1963. This was probably the first really graphic portrayal of the Vietnam War that reached the general American public.

Although these photos left a vivid impression on me, providing my first real exposure to the “face of war” in Vietnam for me, like most of my classmates, the idea of not being able to go to the country after having invested nearly a year of language study to learning Vietnamese was galling. But at the time the Special Forces recruiters showed up, none of the previous graduating class of Vietnamese ASA linguists had been assigned to Vietnam. Most ended up in the Philippines, or at an ASA base in Petaluma or Ft. Meade, probably spending their days emptying classified trash waste baskets, for which they had the requisite clearance. We were appalled at the thought of not experiencing Vietnam after putting in all that effort on the language.

One day mid-way through the course, the Asian languages enlisted students were summoned to an assembly. The company First Sergeant, with a strong Southern accent and evidently not much of a linguist, drawled, “Ah wawnt awl yew min in Thigh, Burmanese, and Vi-etnanese to fall out in the comp’ny ay-ree.” After we had formed in ranks, two Greek gods of Special Forces soldiers appeared, resplendent in their distinctive berets (a recent Kennedy era innovation), creased fatigues, medals flashing in the afternoon sun, and glistening spit-shined boots. The gist of their pitch was that they were recruiting for a super-secret Army Security Agency Special Forces unit. Although they couldn’t indicate its exact function, they made it clear that if you were an adventure freak, this was for you.

Signing up with the ASA Special Forces would mandate an extra year of service beyond the three to which I had already committed because of all the additional training involved. And because of the physical rigor of the training it wasn’t guaranteed that signing up would result in eventually ending up in an ASA Special Forces unit. But, at the time, it seemed like the best option to get to Vietnam and, because of Mai, I had an additional motivation to be assigned there. She would be soon graduating from Georgetown and returning to Vietnam. So, along with four or five others from our class, I trooped down the hill to headquarters and signed up for ASA Special Forces. A few days later, I came to my senses and realized that the extra year was too much and the uncertainties too many. For some reason they allowed several of us to de-enlist. It was, after all, a volunteer unit.

I later learned from Peter Knee (Ông Kính) who went through with it, that the assignment was not as thrilling as we had imagined (though Peter, by force of habit, was still guarded about the details of his ASA Special Forces service even nearly fifty years later). Someone who served in an Air Force unit co-located with a ASA Special Forces unit described the work as tedious and not particularly dangerous.[26] For Ken Woodward, however, the situation was somewhat different. “SGT Ken Woodward come to the 400th ASA SOD [Special Operations Division] around March 1964. He arrived with SSG Peter G. Knee from Language School. Ken Woodward and Peter Knee were Vietnamese Linguists. Ken Woodward was promoted to SSG at the 400th DOD and assigned to the team deploying to Vietnam in April 1965 through October 1965. He met a Vietnamese Lady in Saigon and fell in Love. She worked at the Capital Bar on Tu Do Street at that time. They decided to get married as soon as he could return to Okinawa.”[27] As a consequence, like me Ken lost his cryptographic security clearance and therefore had to transfer to regular Special Forces.

Ken was shot and wounded in the jungle while on operation, and was lucky to escape with his life. On his first mission in Vietnam, and first time ever in the field, he was assigned to do a POW snatch. Ken “ended up in a VC area that had cement bunkers. They got in OK, but they were spotted trying to leave the area. He got shot through the stomach and was lying beside a fallen tree. The VC kept shooting him in his exposed leg, but after about 8 hours a Mike Force team extracted him. He spent more than a year in a military hospital…”[28] Ken tried, but failed, to get an officer’s commission and stay on as a career soldier. Being an inveterate adventurer, he taught himself to fly, but tragically died in an air accident when while performing stunts, he took his plane over the edge of its capabilities.

All of this lay in the future as I completed my language training in Monterey in August 1963, took a month leave, and flew to Vietnam in October 1963, arriving at about the same time as John Buquoi, who was in the mixed NCO-private class, and who features in the following chapter. I believe John and I were the only ones from our September 1962 Monterey class who went directly to Vietnam. And that is where the story of Vietnamese Days really begins.

- [footnote]Stephen L. Keck, “Text and Context: Another Look at Burmese Days,” SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research, Vol. 3, No. 1, Spring 2005, ISSN 1479-8484 , p.32. ↵

- Stephen L. Keck, “Text and Context: Another Look at Burmese Days,” SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research, Vol. 3, No. 1, Spring 2005, ISSN 1479-8484 , pp. 32-33. ↵

- Daniel Yergin, Shattered Peace, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1977), p. 149. ↵

- The Joint Chiefs preferred strategy as formulated at the outset of the Eisenhower era "would place in the first priority the essential military protection of our continental U.S. vitals and the capability of delivering swift and powerful retaliatory blows. Military commitments overseas - that is to say, peripheral military commitments -would cease to have first claim on our resources." Robert B. Bowie and Richard H. Immerman, Waging Peace: How Eisenhower Shaped and Enduring Cold War Strategy," (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 184-185. ↵

- George Herring "Eisenhower, Dulles, and Dienbienphu: 'The Day We Didn't Go to War' Revisited," The Journal of American History, Vol. 71, No. 2 (Sep. 1984). ↵

- Andrea Most, “You’ve got to be carefully taught”: The politics of race in Rogers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, Theater Journal, October 2000, 52, 3; ProQuest, p.338. ↵

- Andrea Most, “You’ve got to be carefully taught”: The politics of race in Rogers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, Theater Journal, October 2000, 52, 3; ProQuest, p.315. ↵

- Andrea Most, “You’ve got to be carefully taught”: The politics of race in Rogers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific, Theater Journal, October 2000, 52, 3; ProQuest, p.314. ↵

- Jayna D. Butler, “You’ve Got to Be Carefully Taught”: Reflections on War, Imperialism and Patriotism in America’s South Pacific, (2013). All Theses and Dissertations. 3812.https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/3812 ↵

- Hsiao Li Lindsay, Bold Plum: With The Guerrillas in China’s War Against Japan, (2005). ↵

- A 1964 profile of Thich Quang Lien states that he usually wore brown robes at Yale. Jack Langguth, “The Buddhist Way in Vietnam,” New York Times, October 11, 1964. My recollection of the bright yellow saffron robe may have been influenced by later images in Vietnam, but the memory of the flowing robe remains quite vivid. The wearing of Buddhist robes of whatever color was a striking sight in New Haven in the late 1950s. ↵

- http://chuaadida.com/chi-tiet-phat-giao-viet-nam-nam-1963-3144/ ↵

- https://clickamericana.com/topics/war-topics/20-questions-about-the-draft-answered-1967 ↵

- https://clickamericana.com/topics/war-topics/20-questions-about-the-draft-answered-1967 ↵

- https://clickamericana.com/topics/war-topics/20-questions-about-the-draft-answered-1967 ↵

- David Card, Thomas Lemieux, “Going to College to Avoid the Draft: The Unintended Legacy of the Vietnam War,” The American Economic Review, Vol. 91, No. 2, Papers and Proceedings of the Hundred Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the American Economic Association. (May, 2001), p. 16. http://davidcard.berkeley.edu/papers/vietnam-war-college.pdf ↵

- “The Military Draft During the Vietnam War,” Resistance and Revolution: The Anti-War Movement at the University of Michigan, 1965-1972. http://michiganintheworld.history.lsa.umich.edu/antivie tnamwar/exhibits/show/exhibit/draft_protests/the-military-draft-during-the- ↵

- Ironically now the Defense Language Institute offers Portuguese, but has dropped Vietnamese. ↵

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia,_South_Carolina ↵

- Basic Training: United States Army Training Center, Infantry. Fort Jackson, South Carolina, Company B, Seventh Battalion, Second Training Regiment, June 1, 1962. ↵

- The actual language is “To separate the barrel and receiver from the stock lay the weapon on a flat surface with the sights up, muzzle to the left. With the left hand, grasp the rear of the receiver and raise the rifle. With the right hand, give a downward blow, grasping the small of the stock. This will separate the stock group from the barrel and receiver group. Place the barrel and receiver group with the bolt closed on a flat surface with the sights down (insuring that the aperture is at its lowest position), muzzle pointing to the left. Holding the rear of the receiver with the right hand, grasp the follower rod with the thumb and forefinger of the left hand and disengage it from the follower arm by moving it toward the muzzle.” U.S. Rifle Caliber .30, M1, FM 23-5 Department of the Army Field Manual, May 1965, p.5. ↵

- Basic Training:United States Army Training Center, Infantry. Fort Jackson, South Carolina, Company B, Seventh Battalion, Second Training Regiment, June 1, 1962. ↵

- For a personal account by Dawson of his D-Day experiences see https://books.google.com/books?id=Y_JwidB9BlcC&pg=PA231&lpg=PA231&dq=Pointe du Hoc "Francis W. Dawson"&source=bl&ots=FY_B--cxMJ&sig=ACfU3U0QiHdm7S6g-0vYQ0PfS04UOlTmVA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjT-czX2KrmAhUlMn0KHfqgDhkQ6AEwAXoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=Pointe du Hoc "Francis W. Dawson"&f=false ↵

- See his citation for the Distinguished Service Cross: “The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, July 9, 1918, takes pleasure in presenting the Distinguished Service Cross to First Lieutenant (Infantry) Francis W. Dawson (ASN: 0-400036), United States Army, for extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations against an armed enemy while serving with Company D, 5th Ranger Infantry Battalion, in action against enemy forces on 6 June 1944, in France. First Lieutenant Dawson led his Ranger Platoon ashore in the invasion of France against heavy enemy artillery, machine gun, and small arms fire. He then personally took charge of the breaching of wire entanglements. When a gap was created, he led his platoon through it and directed them in scaling a 100-foot cliff. Upon reaching the top of the cliff, he, accompanied by one soldier, rushed forward with a submachine gun and destroyed a German pill box, killing or capturing the enemy located therein. First Lieutenant Dawson's aggressive leadership, personal courage and zealous devotion to duty exemplify the highest traditions of the military forces of the United States and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.” https://valor.militarytimes.com/hero/22034 ↵

- https://www.historywiz.com/primarysources/kennedyspeechcuba.html ↵

- Most of his work was airborne direction finding signals intelligence aimed at locating enemy units on the ground. “We used facilities at the base when we were flying but when performing non-flying duties. We worked in Quonset huts at a small Army Security Agency/Special Forces unit away from the air base, the 313th Radio Research Battalion. … Although I flew on twenty-two intelligence-collecting missions while in Vietnam, I spent most of my time at the 313th. We had well built bunkers, lots of barbed wire protection, and machine gun towers, so I felt relatively safe there.” J. David Joyce, Not Quite an Ordinary Life, (iUniverse, 2009). ↵

- John E. Malone, Top Secret Missions.https://books.google.com/books?id=eDHjU9KBpFAC&pg=PA205&lpg=PA205&dq=Ken Woodward ASA special forces Vietnam&source=bl&ots=yKFUeT6m8Y&sig=ACfU3U1ldgaGjZbeeTl7KU5gaB0izSsGXA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi--PT5xKrmAhUHs54KHTjjDooQ6AEwAHoECAwQAQ#v=onepage&q=Ken Woodward ASA special forces Vietnam&f=false ↵

- John E. Malone, Top Secret Missions.https://books.google.com/books?id=eDHjU9KBpFAC&pg=PA205&lpg=PA205&dq=Ken Woodward ASA special forces Vietnam&source=bl&ots=yKFUeT6m8Y&sig=ACfU3U1ldgaGjZbeeTl7KU5gaB0izSsGXA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi--PT5xKrmAhUHs54KHTjjDooQ6AEwAHoECAwQAQ#v=onepage&q=Ken Woodward ASA special forces Vietnam&f=false ↵